In its most rudimentary form, ‘decolonisation’ is the process which signifies the end of rule by a foreign power and the recuperation and/or formation of an ‘independent’ entity, usually a nation-state, through a process often referred to as a ‘transfer of power’. The question that is brought up by influential post-colonial and decolonial scholars like Frantz Fanon, Anibal Quijano and Walter Mignolo, is ‘to whom is power transferred’?

The post-colonial movement began in the 1970s following Edward Said’s work on Orientalism. Through his work, he emphasized the ways in which Western perspectives were categorized as superior to non-Western perspectives. Key concepts related to postcolonialism are useful in understanding how the issue of decolonisation remains relevant today:

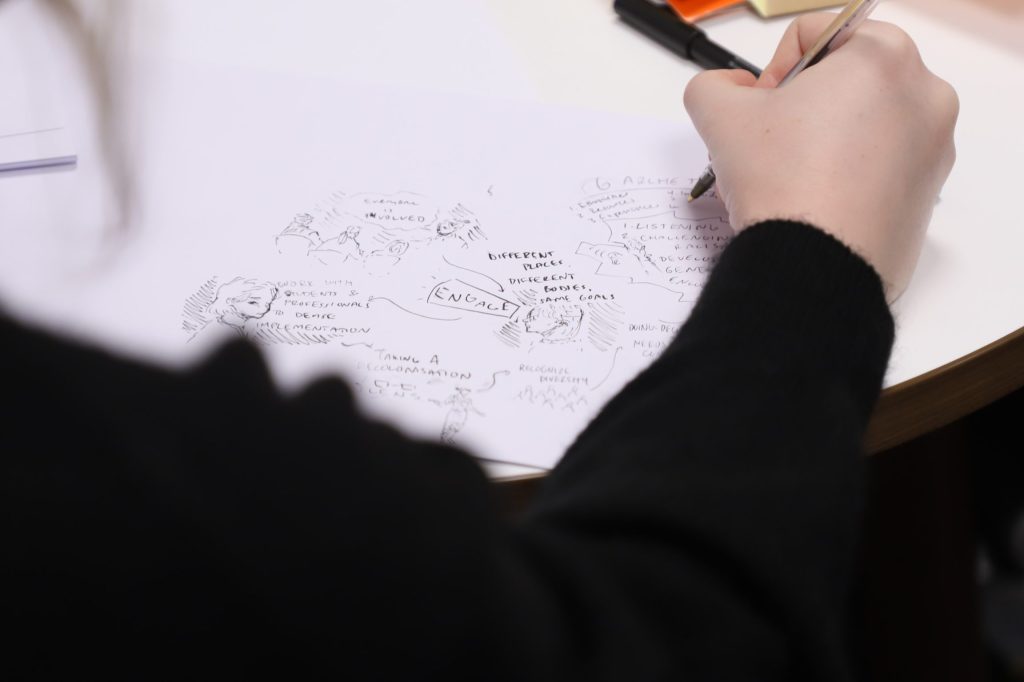

Decolonising, put simply, is about recognising, challenging and dismantling the power structures that oppress the colonised. But everyone’s version of what this means in practice can be different. In their seminal piece, Tuck and Yang (2012) argue that decolonisation is not a metaphor, and shouldn’t be used as a catch-all phrase for making things ‘better’, or ‘more just’. How can we ensure that the decolonising work that we are doing is truly decolonial, truly unsettles, decentres, and redistributes power in a way that seeks to make reparations to the colonised.

- Colonial matrix of power: the legacies of colonialism in structures of power and control, as well as in systems of knowledge. The colonial matrix of power emphasises that many institutional, social, and cultural power relations today can be traced back to structures and cultures implemented during the colonial period (Quijano 2000).

- Coloniality: a concept to describe the social, cultural and epistemic impacts of colonialism. Coloniality refers to the ways in which colonial legacies impact cultural and social systems as well as knowledge and its production.

- Decoloniality: A movement which identifies the ways in which Western modes of thought and systems of knowledge have been universalised. Decoloniality seeks to move away from this Westernisation by focusing on recovering ‘alternative’ or non-Western ways of knowing.

- Neo-colonialism: Recognition that colonisation has not ended, and explains how ongoing forms of colonisation are present in contemporary society (Spivak, 1999; Young, 2003).

This course is intended to act as a starting point to your own enquiry into the question of what decolonisation means for you, and why it is important to you. One place to start, according to Icaza and Vázquez (2018), is understanding their framework of three core processes for decolonising the university: facilitating positionality, practising relationality and considering transitionality.

References

- Icaza, R and Vazquez, R. 2018. Diversity or Decolonisation? Researching Diversity at the University of Amsterdam in Bhambra, G.K., Gebrial, D and Nişancıoğlu, K (eds), Decolonising the University? London: Pluto Press.

- Quijano, A., & Ennis, M. (2000). Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America. Nepantla: Views from South 1(3), 533-580.

- Said, E. W. (1978) Orientalism. New York:Vintage Books.

- Spivak, Gyatri C. (1999) A Critique of Postcolonial Reason: Toward a History of the Vanishing Present. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press

- Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2012). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1(1).

- Young, Robert J.C. (2008) Postcolonialism: An Historical Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.